A World in Blue and White: The Cross-Cultural Story of Portugal’s Azulejo Tiles

How Moorish Art, Persian Cobalt, Chinese Porcelain, and Dutch Innovation Shaped Portugal’s Iconic Tiles

Azulejos are decorative ceramic tiles used on walls, buildings, and churches throughout Portugal. Their distinctive blue and white designs vividly reminded me of Chinese porcelain and prompted me to learn more about their evolution.

Azulejo tiles are a defining symbol of Portuguese art and architecture, but their history is a story of global connections, technological innovation, evolution, and cultural exchange.

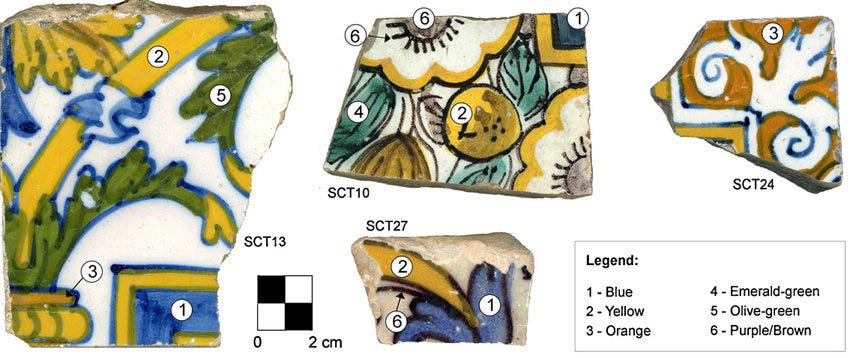

Colours in early ceramics from metal oxides

Early ceramics typically consist of a few colours achieved using different metal oxides: Persian cobalt for blue, copper for green, manganese oxide for purple and dark brown, iron oxide for brown/red/yellow, and Naples Yellow (synthetic lead antimonate) for yellow and orange shades.

The iconic blue from the highly sought-after Persian Blue

The iconic blue and white colour scheme that defines Portuguese azulejos originates in the East. Chinese artisans began using Persian Cobalt Blue pigment, which was highly sought after and widely traded along the Silk Road routes, supplying the Islamic world and China.

Adoption of blue was still early and experimental due to scarcity

While proto-porcelain and early blue and white ceramics existed during the Tang dynasty (7th–10th century), it was primarily via low-fired ceramics, pottery/stoneware (陶), and it was scarce and experimental compared to later periods due to the high costs and scarcity of securing Persian cobalt.

High-fired porcelain only came with the refinement of materials first

High-fired porcelain (瓷) only reached new heights during the Song Dynasty (10th to 13th century) with increased technical refinement of the use of kaolin (white clay) and porcelain stone (petuntse, 白墩子). Kaolin provided whiteness and strength, while porcelain stone contributed to translucency and vitrification.

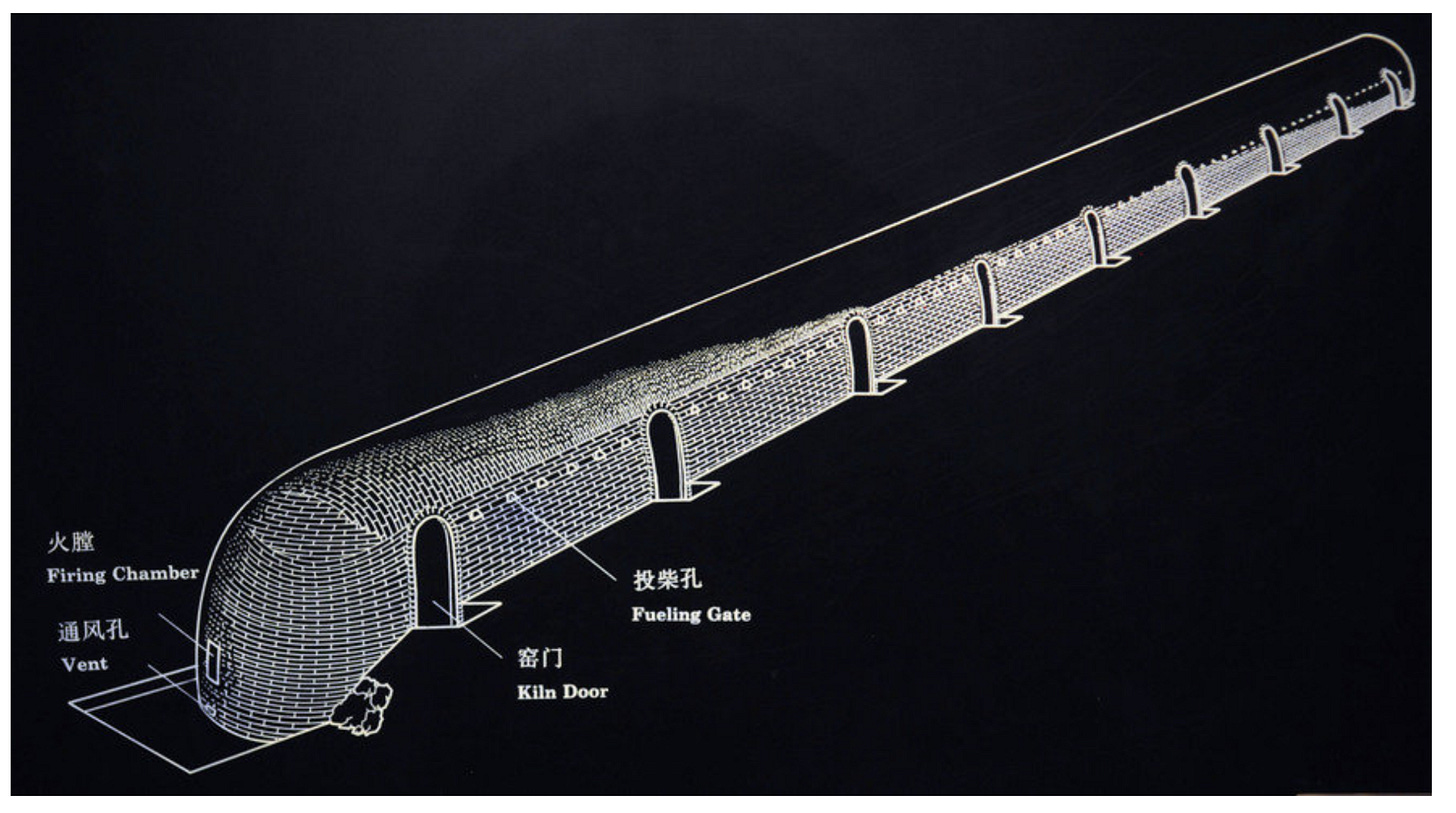

The development of advanced kilns allowed for porcelain to emerge

Developing advanced kilns capable of reaching and sustaining temperatures above 1,200°C (2,192°F) was crucial. These allowed the raw materials to vitrify, producing the hard, white, and translucent qualities that define true porcelain.

Driving the higher adoption of Persian cobalt blue

True blue and white porcelain only became prominent from the Yuan dynasty (13th-14th century). Chinese potters began importing high-quality cobalt blue pigment from Persia and perfecting the underglaze technique.

Chinese blue and white porcelain reached its peak, driving demand amongst the nobles and the wealthy

Only during the Ming dynasty (14th to 17th century), especially in the early 15th century, did blue and white porcelain production reach its artistic and technical peak in China, which became iconic and internationally renowned. These striking blue and white porcelains soon became highly prized in Europe, especially among the nobility and wealthy, and were exported via the Silk Road routes.

Increased availability of Cobalt Blue from European sources lowered prices, drove larger adoption, beyond porcelain to azulejos

From the 16th century onward, cobalt sources were also found in Europe. They were the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains) region of Saxony (now in eastern Germany and the Czech Republic), Norway, and Sweden. These European sources increased availability and lowered cobalt prices. They became significant for the larger adoption of blue pigments in producing glass, ceramics, and azulejos in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Azulejos, first introduced to Portugal by the Moors, started with geometric patterns

Azulejo tiles were introduced to Portugal through Moorish influence (8th-13th century), with the earliest forms appearing in the 13th-14th century. They were heavily inspired by Islamic and Moorish art, which emphasized intricate geometric patterns, interlocking shapes, and arabesques.

The word "azulejo" itself comes from the Arabic "al-zillīj" or "al-zuleique," meaning "small polished stone," reflecting the origin of the craft in the Islamic world.

Royalty adoption sparks popularity amongst the elite

In the 16th century, King Manuel I of Portugal (1495-1521) fell in love with the tilework he saw in Spain. He began importing azulejos for the National Palace of Sintra, sparking their popularity among Portuguese royalty and the elite.

Portugal’s golden age drove incredible wealth creation

The late 15th to 16th century was a golden age for Portugal. It was the age of discoveries and was a transformative era, marked by significant achievements in exploration, empire-building, culture, and governance. Vasco da Gama’s voyage discovered the maritime route to India in 1498, securing Portugal’s dominance over the lucrative spice trade. Pedro Álvares Cabral’s expedition “discovered” Brazil in 1500, laying the foundation for Portuguese colonization of South America, bringing gold.

The Portuguese were the first explorers, before the Dutch and British

Portuguese outposts and trade networks were established in Africa, India, the Persian Gulf, Southeast Asia, and Brazil. Portugal’s early leadership (late 15th to 16th century) in navigation, exploration, and global trade turned it into a leading international maritime and commercial power, profoundly shaping world history before it was eventually overtaken by the Dutch (17th century) and then the British (18th to 19th century).

Azulejos evolving to more colours, complex designs, and narrative scenes

After the 15th century, Portuguese tile-making absorbed influences from Spain (ruled 1580-1640), particularly from Seville, where new glazing techniques like tin-glazing allowed for brighter whites and vibrant blues. The initial focus on geometric and abstract patterns gradually expanded to include more complex designs, narrative scenes, and additional colours.

Adoption of a blue and white palette inspired by the Chinese

Inspired by Chinese porcelain, the iconic blue-and-white colour palette became dominant after the 1620s. This shift was driven by the popularity of imported Chinese porcelain and the desire to replicate its aesthetic designs.

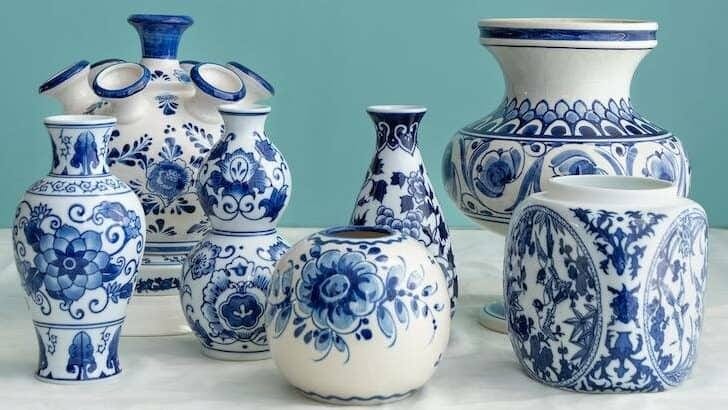

The technological improvement of Dutch Delftware sparked commercialisation and adoption

From the late 17th century onward (1640-1740), the Dutch, particularly in Delft, lacking kaolin clay, developed a local alternative using Dutch clay (yellow or red when fired) dipped into a bath of opaque white tin glaze to cover it completely. They began producing tin-glazed earthenware (Delftware) in blue and white that resembled porcelain in appearance. The hallmark was that it provided a smooth, opaque surface ideal for painted decorations, which was then covered with transparent glaze.

Delftware became renowned across Europe for its quality and artistry. Its blue-and-white tiles became a symbol of prestige and became fashionable among European elites. They were also exported throughout Europe.

Influencing Portuguese adoption and the shift towards their style

Portuguese nobility and clergy were so enamored with Dutch Delftware that they imported considerable quantities to decorate churches, palaces, and aristocratic homes. Portuguese artisans, already familiar with blue from earlier influences, embraced this palette, which became iconic for azulejos in the 18th century.

Their narrative scenes, floral motifs, and landscape designs inspired Portuguese tile makers to move beyond geometric and Moorish patterns toward more figurative, story-telling compositions.

Temporary import bans on Dutch Delftware led to the rise of the domestic Portuguese Azulejos industry

The popularity of Dutch tiles led to a temporary ban on imports in the late 17th century to protect and encourage the local domestic Portuguese tile industry. This spurred Portuguese artisans to adopt and adapt Dutch techniques. This led to a distinctively Portuguese style that retained the blue-and-white palette but developed its large-scale mural compositions and themes.

In summary:

What began as a simple curiosity about Portugal's blue and white azulejo tiles led me on a fascinating journey through centuries of history, culture, and innovation. I discovered that these iconic tiles are not just beautiful decorations, but the result of a vibrant tapestry of global influences-from Persian cobalt and Chinese porcelain to Moorish geometry, Spanish craftsmanship, and Dutch artistry.

The story of azulejos is a testament to humanity’s enduring spirit of creativity, exchange, and adaptation. In every tile, we see Portugal’s unique identity and the echoes of a world connected by trade, discovery, and artistic inspiration, where one can find numerous parallels even in today’s world.

The next time you pass a tiled wall in Lisbon or Porto, you’ll be looking at centuries of global history skillfully painted in blue and white.

The information contained in this article is for general informational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the content, errors or omissions may occur. The author and publisher do not assume any responsibility or liability for any errors, inaccuracies, or omissions in the content, nor for any actions taken based on the information provided. Readers are encouraged to verify any information before relying on it and to seek professional advice as needed.

20 May 2025 | Eugene Ng | Vision Capital Fund | eugene.ng@visioncapitalfund.co

Find out more about Vision Capital Fund.

You can read our annual letters for Vision Capital Fund.

Check out our book on Investing, Vision Investing: How We Beat Wall Street & You Can, Too. We believe the individual investor can beat the market over the long run. The book chronicles our entire investment approach. It explains why we invest the way we do, how we invest, what we look out for in companies, where we find them, and when we invest in them. It is available via Amazon in two formats: paperback and eBook.

Join our email list for more investing insights. Our emails tend to be ad hoc and infrequent, as we aim to write timeless, not timely, content.