Why Inflation and Interest Rates Matter Far Less Than You Think in Investing.

Sensational Financial Headlines.

Financial media often sensationalise with big headlines on inflation:

“Inflation rises 7% over the past year, highest since 1982.” — CNBC

“U.S. Inflation Rate Accelerates to a 40-Year High of 7.5%.” — WSJ

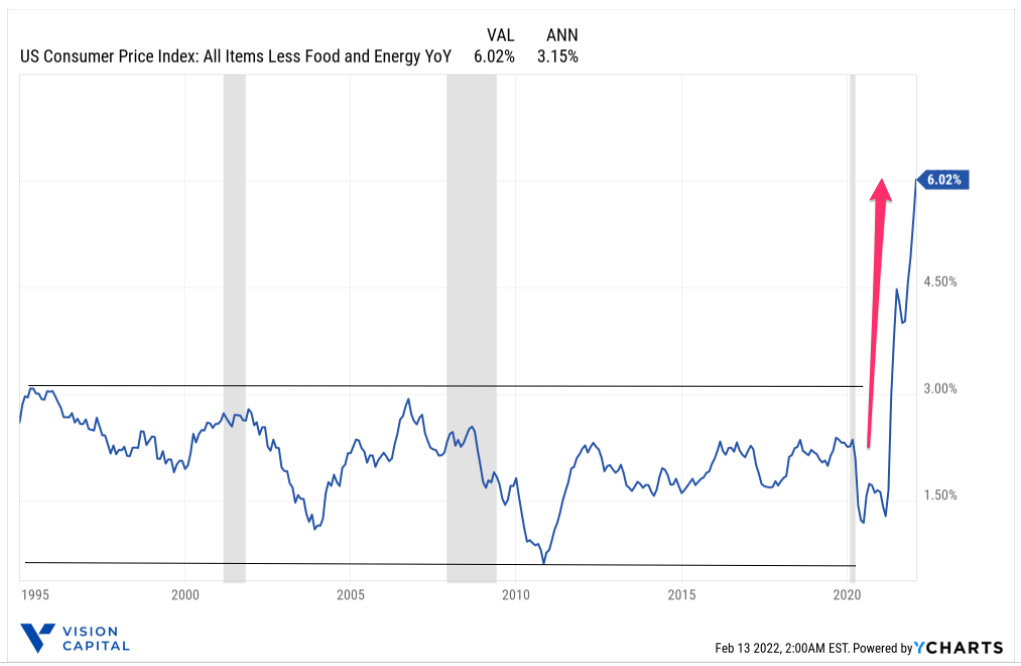

The US Consumer Core Inflation (ex-energy and food) have risen back to almost 40-year highs, above +6% YoY (Dec 2021):

They often follow with similar attention grabbing headlines on rising interest rates and its negative impact on stock markets:

“Inflation, rising rates and the Federal Reserve could whip stocks around.” — CNBC

“Rising interest rates could keep a choke hold on tech and growth stocks.” — CNBC

Zooming out

As long-term investors who are part owners and shareholders of businesses, we wanted to share our thoughts on how we think about inflation, interest rates, and what do we do about it (if any).

A Little Context on Inflation.

First, we are currently in a very different era from the high inflation era of 1965 to 1982, which was largely caused by US Federal Reserve policies that allowed for an excessive growth in the supply of money.

Post 1982, three general reasons largely explained the significantly lower inflation, (1) changes in the structure of the economy, (2) good luck (smaller shocks), and (3) good policy (focus on price stability, etc), which helped to establish far significant lower price stability since (see more here).

Elaborating a little more on some of the more notable changes in the structure of the economy:

For example, since manufacturing tends to be volatile, the shift that occurred from manufacturing to services would tend to reduce volatility.

Manufacturing of goods shifted to just-in-time “JIT” inventory practices, which reduces the volatility of the inventory cycle. This reduced huge price swings to balance less volatile demand vs supply.

Similarly, advances in information technology and communications could have allowed firms to produce more efficiently and monitor their production processes more effectively, thereby reducing volatility in production — and thus in real GDP. Also, more investments have increasingly been in non-physical intangibles than in physical tangibles.

Deregulation of many industries may have contributed to the increasing flexibility of the economy, thereby allowing the economy to adjust more smoothly to shocks of various kinds, thus leading to its greater stability.

Finally, more open international trade, global supply chains, and capital flows may have also helped make the global economy more stable.

Not all Inflation is Even, and the Same.

That said, inflation itself over the last 20 years itself is very uneven. Looking at the US, while most goods-related inflation stayed low, services-related inflation especially that of medical, college and child care skyrocketed.

It is unclear if Fed Monetary Policy can actually keep the rising prices of medical, college and child care at bay, or if they seem to be far more structural in nature, which could require other solutions (for reasons we will not attempt to discuss further, as this is not the intent of this article).

Stocks beat inflation.

Looking at a thirty-year historical chart of the S&P 500 vs US Inflation — Headline and Core (ex-energy and food, which tends to be more volatile), yes inflation might matter in the short-term, but inflation (~2–3% p.a.) clearly matters far less in the long-term vs stocks (~10% p.a.).

It is important to know if structurally longer-term, if we are back to a hyperinflation era of irresponsible monetary, economic & fiscal policies, or not.

Or if it is more caused by temporary supply chain issues (downstream specific to the US and EU), high vehicle prices and high energy prices (due to low base effects).

The former does not seem to be the case to us, at least for now.

Moving on to Interest Rates

In the longer-term context, interest rates (proxied by nominal and real US 10-year Treasury bond yields) have been declining since the peak in 1981.

Interest Rates and Stock Prices

Outlined in our earlier article, “Rethinking Stock Valuation Multiples in time of Lower Interest Rates”. One way to think about it, ceteris paribus (holding revenue, profits, cash flow growth rates, profit margins, etc constant).

Lower interest rates, specifically via lower risk-free rates drives lower cost of equity. Which also in turn drive down lower cost of raising debt. With lower cost of equity and debt, it results in a lower weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

If WACC or the interest rate used to discount future cash flows (e.g. NOPAT, FCF) is lower, the present value of the same future earnings /cash flows should be now worth more, and accordingly higher relative valuation multiples as well.

Below are two examples of how lower risk-free rates drive down cost of equity and debt, and accordingly a lower WACC.

It works similarly vice versa in the case of higher interest rates, resulting in a higher WACC.

Thus academically, lower interest rates should inversely result in higher discounted cash valuations / present values / stock prices. Similarly, higher interest rates should inversely result in lower discounted cash valuations / present values / stock prices, ceteris paribus, all things being equal.

However, that inverse relationship between interest rates and stock prices is not as clear-cut in real life.

As of Feb 2022, the Fed is expecting to hike interest rates quite aggressively for the next couple of years, and the market is starting to price that in as well.

But that said, the market has been consistently wrong over the long-term (~20 years) in pricing where interest rates will go in the short-term.

Why Interest Rate Movements don’t bother us?

Ultimately, for us as long-term investors, whose investment horizons are in years if not decades, interest rates movements, be it hikes or declines, really largely just affect valuation multiples in the short-term.

Valuation multiples may matter a lot more in the short-term, accounting on average ~46% in a 1 year timeframe, but they matter significantly far less, ~5% in a longer 10 year timeframe.

Whereas it is the growth of revenue/sales, profits and free cash flows that ultimately drive long-term stock market returns, accounting for ~54% in a 1 year timeframe, but matter so much more, ~95% in a longer 10 year timeframe.

“Where revenues, profits and cash flows eventually flow, the stock price eventually goes.” — Eugene Ng

In Closing

We don’t think structurally high inflation is here to stay for the long-term (i.e. decades), and accordingly interest rate. We have no idea where interest rates are likely to go in the near-term, though seemingly the direction is more likely higher than lower.

We are focused on only playing the long game in investing, in years if not decades, which is the only one that truly counts.

Compression of valuation multiples due to rising interest rates, which could arise in the near-term are things that are outside our control. What happens is anyone’s guess. We are not market timers, traders, rotators, speculators and certainly not forecasters.

As bottom-up business-focused investors and owners, we do not buy and sell our portfolio companies on the whims and fancies of inflation, or interest rate news, or rotate between sectors or companies that could benefit from such (e.g. higher interest rates, oil prices, etc).

We prefer to spend our time to find and own growing, durable & profitable businesses that are technological disruptive, backed by large addressable markets and durable tailwinds, run by strong management, top dogs in what they do, have operating leverage, and enjoy superior pricing power that can keep increasing prices over the long-term.

That is our inflation and interest rate hedge.

13 Feb 2022 | Eugene Ng | Vision Capital Fund | eugene.ng@visioncapitalfund.co

Find out more about Vision Capital Fund.

You can read my prior Annual Letters for Vision Capital here. If you like to learn more about my new journey with Vision Capital Fund, please email me.

Follow me on Twitter/X @EugeneNg_VCap

Check out our book on Investing, “Vision Investing: How We Beat Wall Street & You Can, Too”. We truly believe the individual investor can beat the market over the long run. The book chronicles our entire investment approach. It explains why we invest the way we do, how we invest, what we look out for in the companies, where we find them, and when we invest in them. It is available for purchase via Amazon, currently available in two formats: Paperback and eBook.

Join my email list for more investing insights. Note that it tends to be ad hoc and infrequent, as we aim to write timeless, not timely, content.