Berkshire Hathaway - The World’s Greatest Serial Acquirer of Businesses

Not just great investors, but also great acquirers of businesses.

The GOAT of Serial Acquirers and Investing

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were previously known to me as one of the greatest investors of all time with Berkshire Hathaway (“Berkshire”). But what became clearly evident to me after reading all 5,300+ pages of the Buffett Partnership Letters, Berkshire Shareholder letters, and AGM transcripts, is that they were not only great business builders, but also fantastic and disciplined risk managers. Through countless acquisitions over decades, Berkshire have become the world’s greatest serial acquirer of businesses.

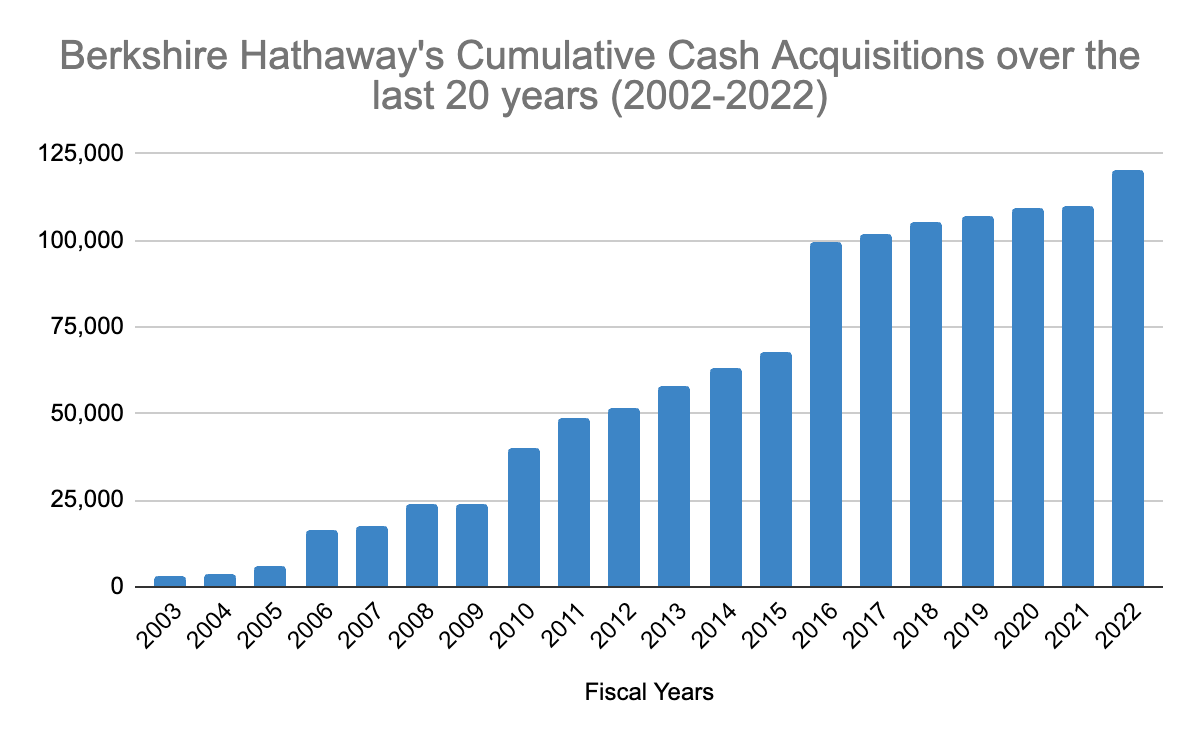

Serial acquirers are companies that acquire wholly owned smaller companies to grow. After reinvesting, they use the surplus cash flows produced by each acquisition to buy even more companies, repeating the process, and compounding shareholder value over a very long time. Including its own acquisition back in 1964, we reckon Berkshire acquired over at least 80 wholly-owned insurance and non-insurance businesses over the last 57 years, and spent in excess of US$120bn on acquisitions over the last 20 years. Berkshire currently has 67 subsidiaries as of Apr 2023. In 2022, the operating businesses generated US$220bn of revenues and US$27bn of operating earnings before taxes, and the insurance business generated US$164bn of float.

In addition to the surplus cash flows from the operating businesses, Berkshire also uses the float of its insurance companies to invest in partial stakes of publicly listed companies worth US$350bn. This insurance float arises because customers pay premiums upfront, and the claims are typically only paid much later. This allows Berkshire to invest much more in higher yielding common stocks than low yielding bonds than most typical insurers. Coupled with a strong disciplined underwriting process and prudent risk management and acquisitions, it provided them with an ever growing insurance float to invest long-term at much higher rates of returns versus their competitors.

Over 57 years from 1965 to 2023, Berkshire has grown to become the 7th largest company in the US by revenues at US$302bn, and the 2nd largest company in the world by total shareholder equity (including banks) at US$472bn.

Berkshire has also grown its market capitalization to US$722bn (as of 28Apr23), generating ~20% p.a. CAGR shareholder returns for over 57 years from 1965 to 2022, beating the S&P 500’s ~10% p.a. hands down, placing it firmly in the “hall of fame”.

Why Berkshire Hathaway now?

Numerous investing quotes from Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger had helped me guide my own investing thinking over the early years of my investing life, allowing me to formulate my very own framework, philosophy and mindset backed by data and logical reasoning.

Surprisingly, I had never read a single investing book on Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, or any of the Buffett Partnership or Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letters and annual reports in its entirety before.

Thus as I have set out at the beginning of the year to make my first ever pilgrimage to the Woodstock for Capitalists, the 2023 Annual Berkshire Hathaway AGM on 6 May 2023 in Omaha, Nebraska, I wanted to read up the entire writings of Warren Buffett, and over 5,300 pages over the last few months I did.

This serves to summarise my learnings and share any key observations that I picked up that were new to me. This is not meant to be a comprehensive primer, but an abstract of my very own observations and learnings. Any errors are solely my fault, and please highlight to me if you see any.

I highly encourage any reader to read the entire Buffett Partnership Letters, Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letters and Annual Reports, together with AGM Q&A meeting transcripts and you will learn much more about investing than you ever will.

It allowed me to understand Berkshire Hathaway better, and gave me a comprehensive overview to reflect upon its success over numerous decades (i.e. 57 years) where the average company lifespan is now under 20 years , to learn from its successes, and to avoid its mistakes.

The Best Investors in the World - Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at Berkshire Hathaway

Warren Buffett (together with Charlie Munger) at Berkshire Hathaway (1965 - 2023) is the best investor in the world, period. It is not just about how high the annualised returns he was investing at, but even more so the extraordinary length of time he kept investing well for. Investing well matters, investing for as long as he did, matters even more, letting compounding do its work. And in compounding, most of the absolute gains are back-handed heavy, and no surprise, 99% of Warren Buffett's net worth was earned after his 50th birthday.

Berkshire Hathaway compounded at a massive ~20% CAGR for 57 years from 1965 - 2022

This is remarkable because there are few to no companies that have lasted so long, and have done so well. That’s why they are really the GOAT (Greatest Of All Time).

That said, over the last 5, 10, 20 years, Berkshire Hathaway has more or less kept in pace with the S&P 500, at about the same or slightly under-perform.

Over the respective time horizons, for 20 years, BRK returned +9.7% vs +10.0% CAGR for S&P 500. For 10 years, BRK returned +10.8% vs +12.4% CAGR for S&P, and for 5Y, BRK returned +7.9% vs +11.1% CAGR for S&P 500.

Because of Berkshire’s present size, making acquisitions that are both meaningful and sensible is increasingly more challenging than it has been during most of their earlier years.

“There’s no question that we cannot do as well as we did in the past, and size is a factor.”

- Warren Buffet (2012 Berkshire Hathaway AGM)

Warren generally expects Berkshire to outperform the S&P in lacklustre years for the stock market, and underperform when the market has a strong year, and this has been largely the case.

That said, most of Berkshire’s businesses are better than the market average, generate strong returns on capital, run by solid managers, with a great company culture. We will elaborate more below in the following sections.

In addition, Berkshire also has certain structural advantages, such as the permanence of shareholder capital base by being publicly listed (though has to pay corporate income taxes), financial leverage from the insurance float, availability to allocate the excess capital of its highly profitable wholly owned operating businesses to acquire new businesses, supplemented by strong disciplined capital allocation decisions.

The Best Capital Allocator and Serial Acquirer of Businesses in the World

There are many serial acquirers that have been hugely successful, and many also don’t do as well. Below are some of the most famous and the largest that comes to mind:

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (EPA: MC, EUR 456bn market cap +24% CAGR 15 years*), a serial acquirer of luxury brands of 28 acquisitions till date ranging from Tiffany, Dior, Bulgari, Sephora and Rimowa.

Danaher Corporation (NYSE: DHR, USD 184bn market cap +19% CAGR 34 years*), focuses across biotechnology, life sciences, diagnostics, environmental and applied sectors, owning more than 20 operating companies.

TransDigm Group, Inc. (NYSE: TDG, USD 42bn market cap +28% CAGR 17 years*) focused on aerospace components, acquiring more than 60 businesses in its first 25 years of operations, and 8 in the last 5 years.

Constellation Software (TSE: CSU.TO, CAD 56bn market cap +36% CAGR 17 years*) focuses on acquiring niche mission-critical vertical market software companies.

But the best, largest and the “OG” (original) of all serial acquirers has got to be Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A, USD 714bn market cap as of 23Apr23, returning +20% CAGR for over 57 years from 1957).

“We also believe that investors can benefit by focusing on their own look-through earnings. To calculate these, they should determine the underlying earnings attributable to the shares they hold in their portfolio and total these.

The goal of each investor should be to create a portfolio (in effect, a "company") that will deliver him or her the highest possible look-through earnings a decade or so from now.

– Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway 1991 Letter

Warren clearly knew what was the north star, to keep growing earnings over the long-term.

Berkshire Hathaway’s List of Acquisitions from 1965-2022

Berkshire Hathaway’s Flywheel

Below is what we think is our best interpretation of Berkshire Hathaway’s flywheel that combines the disciplined, profitable and well-run businesses of the (1) insurance business (run by Ajit Jain) and (2) non-insurance operating businesses (run by Greg Abel), combining with strong culture, and letting solid managers run the businesses well respectively with strong autonomy, in a decentralised format.

Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger are responsible for the overall oversight and capital allocation, with Todd Combs and Ted Weschler are responsible for investing ~11% / ~US$34bn of the overall US$309bn equity investment portfolio under the insurance business.

It is this duo flywheel of Berkshire’s insurance and non-insurance businesses with the insurance float and the surplus capital from operating profits, that allows Berkshire to keep investing in (1) partial ownership stakes of good companies at fair prices, and to keep (2) acquiring durable, predictable profitable, wholly owned companies with able and honest management at the right price.

What does Berkshire Hathaway do?

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is a publicly listed holding company that owns an unmatched collection of wholly and partially owned huge and diversified businesses.

The businesses are split into 4 main segments, (1) insurance businesses conducted on both a primary basis (property, casualty, etc) and a reinsurance basis, (2) the railroad, utilities and energy business, (3) manufacturing businesses and (4) the service and retailing businesses. It is domiciled in Delaware, and its corporate headquarters is in Omaha, Nebraska.

Berkshire’s operating businesses (of 382,000 employees) are managed on an unusually decentralised basis (with only 26 employees at HQ). There are few centralised or integrated business functions.

Berkshire Hathaway owns numerous operating businesses and insurance companies, employing a decentralised management approach, where businesses are given strong operating autonomy, and the ability to make “bolt-on” acquisitions.

Berkshire Hathaway is huge and very profitable.

Berkshire is a gargantuan business. It is the largest company in the world when measured by tangible assets. As of end 2022, total assets are at US$495bn, shareholder’s equity at US$472bn, the stock portfolio which largely resides in its insurance businesses totals US$309bn, and excludes another US$28bn of equity method investments of which ~US$25bn of Kraft Heinz and Occidental Petroleum. Cash balances, including T-Bills are US$128bn, are in excess of US$100bn over the last 5 years. In 2022, it made US$302bn in revenues, US$35bn in operating earnings before taxes, US$19bn of net operating earnings, US$37bn in OCF and US$22bn in FCF.

A good overview and description of Berkshire’s large and diverse group of businesses.

Berkshire Hathaway is still growing and owns a very profitable collection of businesses

In aggregate in 2022 alone, Berkshire generated ~US$302bn in operating revenues for both its insurance and non-insurance businesses, generating ~US$34.7bn in operating earnings before taxes of about ~11%+ profit margins and ~6-7%+ of pre-tax ROE (EBT / Shareholder Equity). Note this excludes the mark-to-market gains and losses of investments that now flow to income statements instead of shareholder equity from 2017 onwards.

This strong profits illustrates the remarkable profit generating power of Berkshire’s group of operating businesses. More important to note, the revenues and profits have been continuously growing, and at high single digit growth rates of ~7% and ~9% CAGR respectively over the last 3 years.

Berkshire Hathaway’s ever growing revenues and operating cash flows since 1992 to US$302bn and US$37bn in 2022 through reinvestment and acquisitions.

“...our goal is to buy really good businesses, and big businesses, and businesses where we like the management, and businesses that we think we can grow over time. I mean, Berkshire is about building earning power.” - Warren Buffett (2013 BRK AGM)

The Non-Insurance Operating Businesses

Looking at the other 5 lines of non-insurance operating businesses, they have consistently grown revenues and profits (earnings before taxes) fairly steadily at low-mid single digits of ~3% and ~4% CAGR over the last 5 years. Notably this group is a very profitable set of solidly profitable businesses that are generating ~11-12%+ EBT margins on a blended basis.

The railway business of BNSF is the gem here, generating ~30%+ margins, which is no surprise why Berkshire has been reinvesting lots of capex back into it, especially over the last few years. Notably, the McLane distribution business notably operates on lower <1% EBT margins. Excluding McLane, overall EBT Margins are much higher at ~15-16%+.

Berkshire’s Insurance Business

Berkshire’s property/casualty (“P/C”) insurance business has been the engine propelling Berkshire’s growth since 1967, the year they acquired National Indemnity and its sister company, National Fire & Marine, for $8.6 million. Today, National Indemnity is the largest P/C company in the world as measured by net worth.

Warren and Charlie like positive float businesses, and were instantly attracted to the attractive business model of the P/C business. P/C insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims only much later (not months, but years/decades). In extreme cases, such as claims arising from exposure to asbestos, or severe workplace accidents, payments can stretch over many decades.

This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums of money i.e. “float”, which they get to invest for their own benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as Berkshire’s insurance business grows with more premiums, so does their insurance float. Yet the trick is consistent disciplined underwriting over the long-term, to underwrite policies once when the pricing makes sense relative to the claims.

This similar “float” concept is also applied by Berkshire to buying wholly-owned businesses which are already profitable (not loss making), so that Berkshire can enjoy and deploy the subsequent excess capital from profits after capex reinvestment, to invest in better opportunities elsewhere and acquire new companies.

There exists no rival insurance operation on the planet to Berkshire’s. There isn’t a close second. Berkshire’s collection of insurers underwrites property/casualty insurance and reinsurance through three groups and combined is the highest rated insurance operation in the world.

GEICO was doing well from 1993 onwards, but lagged Progressive over the last 6-7 years

GEICO underwrites directly marketed private passenger auto insurance and is the second largest auto underwriter in the US with 14.3% market share. GEICO and Progressive are both taking market share from State Farm, who not long ago had 25% of the auto market in the US. Both companies are likely to pass State Farm’s 15.9% share in the next three or four years. GEICO operates with a significant cost advantage of selling direct to customers, largely with no agents or brokers involved in distribution. Paying a gecko is cheaper than paying agent commissions, thus GEICO’s underwriting expenses are at a far lower portion of premiums earned than the competition.

That said, GEICO is severely behind Progressive in using technology in underwriting and claims management, specifically in telematics, or the use of GPS in monitoring cars and driving habits to help properly rate risk and in setting premiums. While the gap can be closed, Progressive has been more profitably gobbling up market share and may pass GEICO in the coming years. GEICO maintains a huge cost advantage over the field but needs to work on this. Management is aware.

Using the Insurance Float to Invest Well

Since 1967, the insurance float has grown over 8,000-fold through acquisitions, operations and innovations to US$164bn (Dec22). It has continued to grow exponentially organically and with acquisitions (latest was Alleghany) at 8% CAGR over the last 12 years (2010-2022).

By design, the float should not decline by more than 3% in any given year, due to the nature of the contracts, allowing for any intermediate or near-term cash demands to compromise their financial strength. This insurance float has been an extraordinary asset for Berkshire Hathaway allowing them to capture higher investment returns in common stocks over time.

There can be a run on banks if deposits decide to flee en masse. There cannot be a run on insurance companies, as the insurance premiums have already been paid upfront by the customers. Most often insurance companies only do poorly, when they don’t underwrite the risks well, resulting in significantly higher than expected claims later, and/or invest poorly resulting in losses/write-downs.

For the P/C industry as a whole, the financial value of the float is far less than it was for many years, as claims far exceed the underlying returns from the float less other expenses. Most of it result from two reasons, (1) poor underwriting (large claims versus premiums) or (2) poor investing/asset allocation via mostly high grade bonds, or to seek riskier higher yields investments, by extending to lower quality bonds (non-investment grade) and non-liquid alternative investments (private equity, real estate, venture capital and hedge funds) which most are ill-equipped to play.

Berkshire significantly differs from the industry with its excellent underwriting record due to its disciplined risk evaluation to avoid being drowned by poor underwriting results. Berkshire has operated at an underwriting profit for 18 of the last 20 years, the exceptions being 2017 (US$3.2bn loss) and 2022 (minimal). For the last 20 years, their pre-tax gain was US$29.2 billion.

Berkshire is famous for their willingness to walk away from underwriting when prices are inadequate. Markel and Fairfax are often compared to Berkshire in structure, but Markel only invests ~15% of total assets in equity securities (US$7.7bn vs US$49.8bn), Fairfax ~8% (US$7.4bn vs US$92bn) compared to a significantly higher percentage ~46% for Berkshire (US$336bn in equity securities vs US$725bn of total assets).

Berkshire has a plethora of investment opportunities from investing in either wholly owned controlling businesses or partially owned stakes in publicly listed companies. In turn, their strategy to acquire businesses that have consistent earnings power, good returns on equity, run by able and honest management have done well. They can in turn use the surplus capital from the businesses to acquire new businesses.

The excess cash reserves combined with Warren Buffett’s ability to make investment decisions very quickly, has also allowed Berkshire to make very highly asymmetric investments with limited downside during market crashes and downturns (e.g. Goldman Sachs, Bank of America with preferreds, etc).

The Financials of the Insurance Business

Looking at the insurance business first, GEICO, Reinsurance, and Property & Casualty Insurance (P/C) generated ~52%, ~30% and ~18% of US$74bn of underwriting revenues respectively, and have been growing steadily at ~12% CAGR over the last 5 years. Sometimes underwriting earnings can be positive, which means Berkshire is paid to do business.

The gem here is Berkshire’s investment asset allocation, generating stable investment income of US$5-7bn+, providing the company surplus capital to keep reinvesting into common stocks.

Understanding the Profitability Dynamics of Insurance vs Non-Insurance Businesses

Though Insurance & Others generates ~83% of revenues, because it is a lower ~9-10% EBT margin business, it generates ~65-70% of EBT. On the other hand, the Railroad, Utilities & Energy business is a higher margin business, despite accounting for ~17% of revenues at 20%+ EBT margins it accounts for ~30%+ of overall EBT.

From a Return on Equity (ROE) (using EBT not Net Income) standpoint, though the Railroad, Utilities and Energy business has a stronger and fairly consistent ROE of ~9%, with the lower Insurance & Other ROE of 5-6%+, the overall blended ROE has been is around ~6-7%.

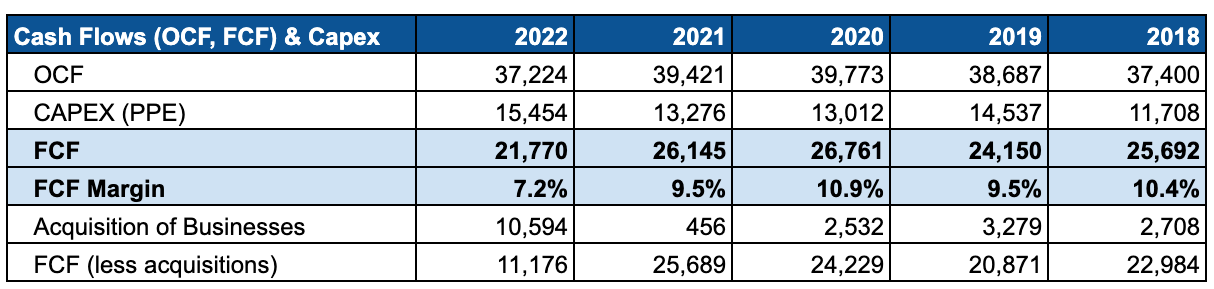

Berkshire’s Growing Cash Flows - OCF and FCF

Berkshire Hathaway with its non-Insurance Businesses have generated about US$36-39bn of Cash from Operations (OCF) over the last 5 years on average.

Berkshire had spent between US$12-16bn of capital expenditures annually over the last 9 years. Notably that in 2022, Berkshire made a sizable acquisition of Alleghany Corporation, a mini-Berkshire, which operates property and casualty insurance and reinsurance businesses and owns manufacturing and service businesses in Oct 2022 for US$11.5bn. It had US$19.7bn cash and investments, US$2.3bn debt, US$14bn float, US$435mil written premiums, US$2.4bn revenues and US$216mil net earnings.

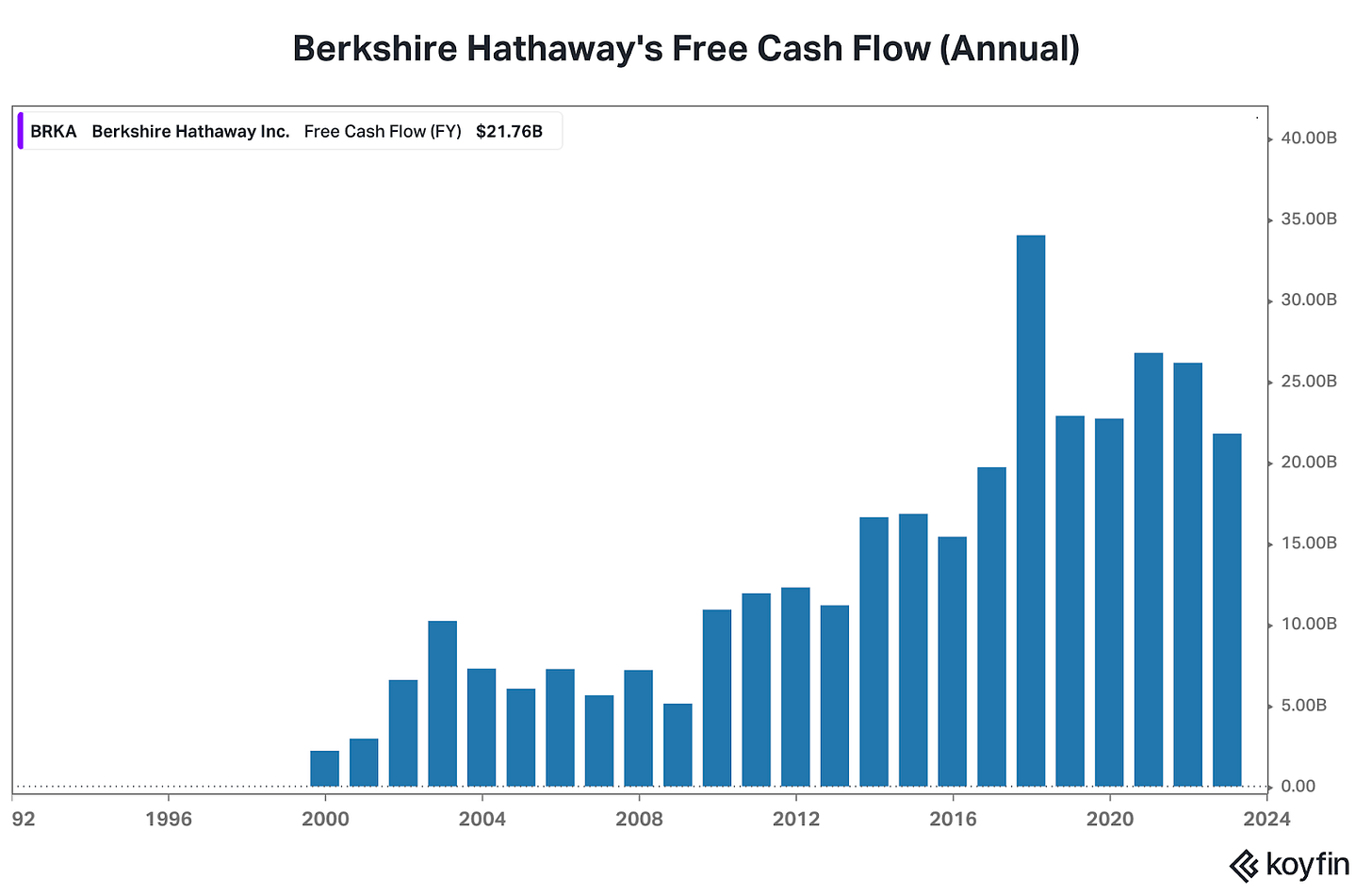

Berkshire has generated north of US$20bn of Free Cash Flow (FCF) over the last 6 years in a fairly consistent and durable manner.

Berkshire continues to grow its long-term investment value via three key ways:

1 | Reinvestment and Acquisition of Controlled Businesses

“The first is always front and center in our minds: Increase the long-term earning power of Berkshire’s controlled businesses through internal growth or by making acquisitions. Though internal opportunities deliver far better returns than acquisitions. The size of those opportunities, however, is small compared to Berkshire’s available excess resources.”

“We constantly seek to buy new businesses that meet three criteria. First, they must earn good returns on the net tangible capital required in their operation. Second, they must be run by able and honest managers. Finally, they must be available at a sensible price.”

2 | Purchase of non-controlling partial stakes in Publicly Listed Companies

“Our second choice is to buy non-controlling part-interests in the many good or great businesses that are publicly traded at a fair price.”

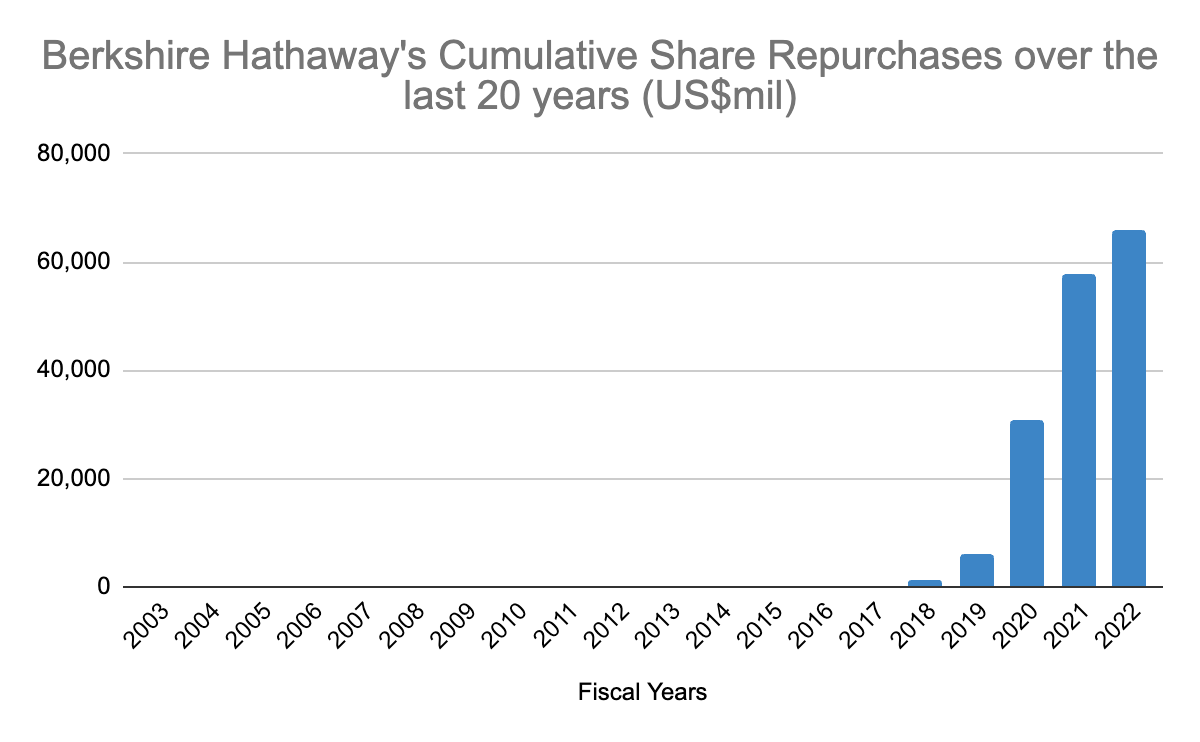

3 | Conduct share buybacks when prices are oversold and attractive (more recent since 2018)

“Our final path to value creation is to repurchase Berkshire shares. Through that simple act, we increase your share of the many controlled and non-controlled businesses Berkshire owns. When the price/value equation is right, this path is the easiest and most certain way for us to increase your wealth.”

Berkshire’s Strong Cash Flow Generation allowing for Acquisitions

Berkshire has generated over US$496bn of Cash from Operations (OCF), spending US$189bn of capex, and in turn over US$307bn of Free Cash Flows (FCF) over the last 20 years.

Which in turn Berkshire has used to spend over US$120bn on cash / controlled acquisitions over the last 20 years.

Using its ever growing and sticky insurance float, Berkshire has invested over US$139bn in Marketable and Equity Securities over the last 20 years.

Berkshire’s cumulative share repurchases started only recently the last few years since 2018, and have totalled US$65.8bn thus far.

The Management

Warren Buffet (CEO and Chairman, age 92) and Charlie Munger (Vice Chairman, age 99) are responsible for all capital allocation and major investment decisions. All of the insurance float, operating float, and occasional derivatives float are reinvested into largely either 100% controlling businesses or publicly listed stocks. Warren Buffet currently still owns 38.5% that is valued at US$113bn and Charlie Munger owns 0.7% that is valued at US$2.1bn (as of 22Apr23).

Warren had pledged in 2006 to distribute all of his Berkshire Hathaway shares – more than 99% of his net worth to philanthropy via 5 foundations. As of June 2021, ~50% has already been distributed. Upon his death, ~99.7% of his estate will go to philanthropies and as taxes to the federal government. The remaining will go to his wife, of which 90% will be invested in S&P 500 ETFs, and the remaining 10% in treasury bills.

Gregory Abel (age 60) is Vice-Chairman of the non-insurance operations, and Ajit Jain (age 71) is Vice-Chairman of the insurance operations, both of whom were elected in 2018.

Gregory (“Greg”) Abel was from MidAmerican Energy Holdings (MEHC) with Walter Scott and Dave Sokol, which Berkshire acquired in 2002, who then ran the Regulated Utility Business, then Berkshire Hathaway Energy (“BHE”). Should a replacement for Warren Buffett be needed, the Board has agreed that Gregory Abel should replace him.

In June 2022, BHE acquired the non-controlling 1% interest held by Gregory Abel for US$870m (at implied US$87bn valuation). In turn, Greg in turn purchased a large block of Berkshire and as of Apr23, owns US$113m of Berkshire shares. I would not be surprised if Greg does not buy more Berkshire shares out of his own pocket over time.

Ajit Jain was hired in 1986, without any experience in the insurance business. Ajit ran the reinsurance business, before taking over General Re (acquired in 1998) after Tad Montross retired in 2016, running it for 39 years. Since then, Ajit has created tens of billions of dollars of shareholder value with the reinsurance business.

Ajit’s forte is his excellent risk management and discipline in preventing foolish losses, allowing Berkshire to amass an sizable reinsurance float with remarkable underwriting profits in a tough insurance industry that largely tends to generate little surplus capital relative to premium. This has allowed Berkshire to become the world’s largest property casualty insurance company by net worth over time. As of Apr23, Ajit owns US$156m of Berkshire shares.

Separately, two investment managers, Todd Combs (age 52) Ted Weschler (age 60), who were both ex-hedge fund managers, joined Berkshire in 2010 and 2012 respectively. Both currently manage a combined total of US$34bn of stocks investments under the insurance business, ~10% of the US$350bn publicly listed equity investments (as of 31Dec21), and other pension assets. Most of their stock investments tend for now to be on the smaller side, and below the threshold to be listed in the annual shareholder letters. Notably, Todd Combs is also the CEO of GEICO temporarily for now.

“...with both Todd and Ted, Charlie and I were struck by, not only a good record, but intellectual integrity and qualities of character, a real commitment to Berkshire, a lifelong-type commitment.

And we’ve seen hundreds and hundreds of good records in our lifetimes; we haven’t seen very many people we want to have join Berkshire.” - Warren Buffett

Source: 2011 Berkshire AGM

Warren and Charlie believe that Todd and Ted both have the brains, judgement and character to manage the entire Berkshire investment portfolio when either of them are no longer running Berkshire. Both of them will also be supporting, and be helpful to the next CEO of Berkshire in making acquisitions.

They are each paid a salary of US$1m a year, and paid 10% of their portfolio outperformance against the S&P 500, of which 80% will come from their own and 20% from their partner’s, incentivising collaboration and cross-sharing of ideas.

Todd Combs joined Berkshire in 2010. Todd was CEO and Managing Member of Castle Point Capital, a long-short hedge fund focused on the financial services sector launched in 2005, pulling a 34% cumulative net return. Interestingly, his portfolio Castle Point was fairly diversified with 27 holdings, with the top 10 accounting for ~57% of the portfolio, and notably most of it was largely in Financials, Insurance and Banks.

Todd was introduced by Charlie Munger to Warren Buffett, and was the first investment manager to be hired at Berkshire. His expertise in investing in finance companies clearly stood out. I would not be surprised that the investments in Nu Holdings and StoneCo were made by Todd.

“Todd has the advantage that he’s been thinking about financial companies like Berkshire for a great many years. That’s useful for us to have around.” - Charlie Munger

Source: 2010 Berkshire Hathaway AGM

Before joining Berkshire in 2012, Ted Weschler was the general partner at Peninsula Capital Advisors, which he started in 2000. Weschler's track record was outstanding, producing total returns of +1,236% during its first 11 years of life, outperforming the S&P 500 by +1,259%, growing assets under management from US$400m to US$2bn. It held on to four of its original 13 positions during that period, and two of those were huge winners.

Interestingly, most were obscure names, Cogent Communications jumped 13X and WR Grace & Co. Peninsula (his first employer) jumped 11X. The other two were DaVita and WSFS Financial. Notably his portfolio back then was fairly concentrated with only 10 holdings and the top 4 accounting for ~82% of the portfolio. Notably, Ted also did very well on his personal front, snowballing his Roth IRA retirement account from US$70,000 to US$264m in under 30 years as of 2018.

Source: Seeking Alpha, Manual of Ideas

Discussing and understanding the top management at length is important for succession planning, given Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s age (92 and 99 respectively), and one should be able to glance, if Berkshire’s culture and discipline can continue even in their absence.

Culture - Having the right people to make sure that happens

Warren and Charlie have been very intentional in making sure that they hire the right people to run the various businesses, and with succession planning as well.

The Board of Directors understand that Berkshire’s culture is 99.9% of running the business. They don't think that having meetings of committees and bringing in outside experts or anything like that.

The principles that have been employed to date in running Berkshire should continue to guide the managers who succeed Warren Buffett, and I do reckon that their unusually strong and well-defined culture is very likely to remain intact and persist.

Fortress Balance Sheet

At the parent level, Berkshire Hathaway has a fortress balance sheet with only US$21bn of debt versus US$20bn of cash and T-bills and over US$477bn of investments with US$495bn of book value (Dec 2022 vs US$713bn market cap as of 23Apr23).

No surprise, it has an AA rating from S&P. Notably that there is a total of ~US$122bn of debt, of which ~US$76bn belongs to the railroad/BNSF and utility/BHE operations, and that debt is not guaranteed by the parent, thus it is not hypothecated to the parent, and it is not Berkshire's obligation.

Berkshire Hathaway’s Low Cost of Debt ~3-4%

Berkshire’s strong balance sheet and AA / AA+ S&P credit ratings allows it to raise debt at opportunistic times during low rates and for long-tenors (decades).

Berkshire’s Stock Investment Portfolio: Diversified by count, Concentrated by holdings

The fair value of the stock portfolio is US$350bn as of 31Dec21, and US$308bn as of 31Dec22. For their US holdings alone, from the 31Dec22 13-F, they own a total of 49 holdings.

The top 5 positions account for 75% of total fair value of equity securities, and the top 10 positions account for ~89% of US fair value.

The largest being Apple which accounted for ~39%, followed by Bank of America ~11%, Chevron ~10%, Coca-Cola ~8% and American Express at 7%.

What should be evident from the top 16 positions, it is littered with many multi-baggers held over long periods of time (~7 year holding period for top 10).

Power laws were clearly evident, as a few winners accounted for the majority of absolute returns, the 6 holdings alone, Apple, AMEX, BAC, BYD, Moody’s, Coca-Cola, accounted for ~91% of the absolute gains.

“The lesson for investors: The weeds wither away in significance as the flowers bloom.

Over time, it takes just a few winners to work wonders” - Warren Buffett

Apple was the largest from an absolute perspective of US$130bn of gains as it was a 5X. Many other multi-baggers include Moody’s 38X, BYD 33X, American Express 19X, and Coca-Cola 18X. Concentration is an outcome over long periods of time, not a strategy.

Note that if Berkshire were to liquidate the entire portfolio immediately, they would have to pay significant capital gains taxes. Another major advantage is that Berkshire being very long-term focused, and not trading the investment portfolio unlike most investment professionals, it does not have to constantly pay capital gains taxes.

This in turn creates a deferred tax liability that is only paid when the stocks are sold, and the profits realised. It is this deferred paying of capital gains taxes that has allowed Berkshire to compound their investment returns at even higher rates.

Also do take note that Berkshire pivoted more from its stock portfolio in 1998. It acquired General Re in 1998 which reduced the stock portfolio concentration from 115% of book value and 65% of assets to 65% of book value and 30% of assets. The pivot allowed Berkshire to divert material proportionate surplus capital away from common stocks to wholly-owned businesses such as what are now BHE and BNSF.

Investment Allocation by Sector - The Tech Investor

The three largest sectors are Information Technology, Finance and Consumer Staples. Finance allocation stems from Buffett’s early experience with GEICO, National Indemnity and Illinois National Bank.

Warren’s stronghold on consumer staples seemingly stem from Coca-Cola, and his realisation of the power of strong brands came from the growth of low-capital chocolate maker See's Candy (acquired in 1972), which was from Blue Chip Stamps.

But it was Charlie Munger that really got Warren Buffett to change his mindset from buying “cigar butts” or lousy companies for cheap, to buying good companies at fair prices.

Also to take note that the sector allocation has steered away from consumer staples to more information technology since 2012. Note that Berkshire only started buying Apple in Q1 2016 onwards. Finance has generally been a large allocation, though fluctuating over time. Energy has also seen a small but growing notable allocation with Chevron and Occidental Petroleum more recently over the last few quarters.

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger - The Investors

A common observation is that both Warren and Charlie tend to focus on already profitable businesses with growing, fairly durable, and predictable revenues, but could be fair valued, or at times even undervalued. Using Buffett’s favourite Aesop fable, this meant that they were often more likely to get back their two birds in the bush.

Their ability to get a rough sense of the higher probability of the expected earnings coupled with the discipline to not overpaying and buying at fair to cheap prices, meant that there was a good margin of safety, and no surprise the stock investment portfolio tends to be well anchored/outperform during market sell-offs, and either market-perform to underperform during market rallies.

Historical Performance of Berkshire’s Equity Portfolio: 7-8%+ CAGR

Chris Bloomstran who runs Semper Augustus Investment Group, whom I met at MOI’s The Zurich Project last year 2022 writes up one of the most detailed analysis and breakdown of Berkshire Hathaway that I know in his annual shareholder letter.

He estimates the Berkshire equity investment portfolio returned ~7-8% CAGR (+7.3% / +8.0%) since 1999, outperforming the S&P 500’s +6.9% by a whisker. Particularly the single holding of Apple which has returned 5X on cost since its first purchase in 2016, has accounted for a significant portion of the equity portfolio’s outperformance in recent years.

Given the top 5 positions of (Apple ~39%, Bank of America ~11%, Chevron ~10%, Coca-Cola ~8% and American Express at 7%), I would not be surprised for the equity investment portfolio to return similarly 7-9%+ CAGR over the long-term as well, edging the S&P 500.

Equity Method Investments - US$28bn (US$13bn Kraft Heinz & US$11bn Occidental)

Berkshire and its subsidiaries hold investments in certain businesses that are accounted for pursuant to the equity method. Currently, the two most significant are Kraft Heinz (26.6% share) and Occidental Petroleum (21.4% share), which excludes the potential effect of the exercise of Occidental common stock warrants. The others (~13%) are Pilot Flying J (38.6% interest), which has 800 travel centre locations across the US and Canada, generating US$50 billion in revenues. Another 41.4% interest was acquired in Jan 2023. and Berkadia (50% interest) which provides capital solutions, investment sales advisory and mortgage servicing for multi-family and commercial real estate.

Kraft Heinz manufactures and markets food and beverage products, including condiments and sauces, cheese and dairy, meals, meats, refreshment beverages, coffee and other grocery products.

Occidental Petroleum is an international energy company, whose activities include oil and natural gas exploration, development and production, and chemical manufacturing businesses. Occidental’s midstream businesses purchase, market, gather, process, transport and store various oil, natural gas, carbon dioxide and other products.

Accounting - Berkshire’s stated book value is lower versus its actual intrinsic value

Note that Berkshire’s book value was much more reflective of its intrinsic value in the earlier years, and became less so as their focus shifted in the early 1990s to buying more wholly owned businesses.

GAAP accounting for control companies versus stock holdings creates a disconnect in the valuations of Berkshire’s wholly owned operating businesses, as the former is only written down, but never revalued upwards.

Over time, this widens the gap between Berkshire’s intrinsic value and its book value (see below). This is important because over time, stock prices gravitate towards intrinsic value, and Berkshire’s book value which was historically a good reflection of intrinsic value had become less relevant.

Accounting - Notably Berkshire’s reported GAAP Earnings are misleading because stock investment gains and losses flows into the income statement

Starting 2017, the new GAAP accounting rule required that the net change in unrealized investment gains and losses in stocks that Berkshire holds must be included in all net income figures. Because market movements are volatile, this significantly distorts and makes any reading of Berkshire’s “bottom-line” of operating profits or net income from 2017 onwards totally “useless” (see below). Instead focus on Berkshire’s operating earnings, and more importantly, its normalised per-share earnings power.

Drivers of Long-Term Stock Returns - Earnings

In the short-term, valuation multiples accounting for most of the market movements, and either expand or compress, depending on whether Mr Market is feeling euphoric or is experiencing depression.

But over the long-term, it is the growth of earnings on a per share basis over time that ultimately drives long-term stock market returns.

If a business is growing earnings 5% CAGR for the next 20 years, don’t expect to make 15% or even 25% CAGR, unless valuations are ridiculously cheap.

It is that simple, we wrote about it here as well, but few have the temperament to hold through the price volatility, and to not allow the price narrative to influence their business narrative.

“You cannot expect to forever realise a 12% annual increase, much less 22% in the valuation of American business, if its profitability is growing only at 5%.

The inescapable fact is that the value of an asset, whatever its character, cannot over the long term grow faster than its earnings do.

This is a critical fact often ignored--that investors as a whole cannot get anything out of their businesses except what the businesses earn.

The absolute most that the owners of a business, in aggregate, can get out of it in the end--between now and Judgment Day--is what that business earns over time.”

- Warren Buffett (1999 Fortune Magazine)

Not doing a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Valuation

Think in DCF models about the earnings of the business, but don’t actually do one. We are not interested in finding out the current intrinsic value, which involves multiple inputs to make any investing decision, and keeps fluctuating over time.

Over time, stock prices gravitate toward intrinsic value. Instead of calculating the exact intrinsic value, we instead are more interested in the range of the growth path of Berkshire’s future intrinsic values. We rather be approximately right, than to be precisely wrong.

Thus in the same light and spirit, we really don’t need to do a DCF valuation to be able to roughly estimate the future expected returns of an investment in Berkshire at current valuations.

“I’ve never seen you know, Warren talks about these discounted cash flows. I’ve never seen him do one.” - Charlie Munger (1995 Berkshire AGM)

“...we do not sit down with spreadsheets and do all that sort of thing. We just see something that obviously is better than anything else around, that we understand. And then we act.” - Warren Buffett (2009 Berkshire AGM)

Thinking about Berkshire Hathaway’s Future Returns

Berkshire has major ownership in a great and unmatched collection of huge and diversified businesses with strong cash generation abilities, talented managers, and a rock solid culture. It remains in good shape for whatever the future brings. It will not be our highest performing investment, but it is one of the most knowable.

Hopefully by now, you can understand Berkshire and its component parts (insurance, operating business and its investment portfolio), and understand that the growth in share price should match the underlying growing economics of the business over time.

Berkshire, like any company, should expect the total shareholder returns from the stock to roughly match the returns from the business on a per share basis over time, of revenues, earnings, and cash flows. Only if the business is growing, then one can expect growing returns.

“Where revenues, earnings and cash flows go, eventually the stock price flows” - Eugene Ng

None can dispute that Berkshire’s extraordinary years are gone. I think it still has a pretty shot at many more good years to come, and on edge should beat the S&P 500 over the long-term. Most importantly with little downside, due the strong quality of the underlying businesses both on the insurance and the non-insurance side, run by strong managers. Instead when markets tumble, expect Berkshire Hathaway to do relatively well and outperform, just like in 2022 and many times before.

“It won’t be the highest compounder, by a long shot, against many other businesses.

I think it will be one of the safest ways to make decent money over time.”

- Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway 2019 Annual Meeting

Berkshire pays no dividend so the shareholder returns are all derived via the stock price, and should roughly match its return on equity (~7%+) over time, plus or minus any expansion or contraction in valuation multiples.

Add in the expected +7-9% CAGR in its equity investment portfolio, and any share repurchases bought at reasonable prices (120-150% of Book Value), I would not be surprised for Berkshire to still provide good returns of 7-9%+ CAGR for the foreseeable future versus the S&P 500’s typically 5-7%+ long-term CAGR .

If I did not invest my own capital in single name stocks, and have a minimum return hurdle threshold of 25% CAGR, instead of investing in an S&P 500 ETF and own 500 companies, I would probably invest in and own Berkshire Hathaway in a heartbeat, with its fairly high degree of certainty of a 7-10% long term CAGR.

It is through spending these few weeks and writing this, that I have come to truly appreciate the magic that Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger and the Berkshire team of over 382,000 employees have come to achieve over the last 58 years.

Though I have never owned Berkshire Hathaway, but after doing a deep dive, and recognizing its durability and compounding power of disciplined capital allocation and acquiring of good businesses, who knows, I might just change my mind when the price is right. As I always remind myself to have strong opinions, but loosely held. This sure did.

“You have to keep learning if you want to become a great investor.

When the world changes, you must change.”

- Charlie Munger in 2022 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter

If you are still interested to read on more, below captures a short snippet of Warren and Charlie’s early investing journey to the modern day, Berkshire Hathaway. It is not meant to be comprehensive, but captures the major pivot points as their path converge over time.

Warren Buffett and The Buffett Partnership (1957 - 1969)

Warren Buffett was born in Omaha, Nebraska, August 30, 1930. He came from a business family. His grandparents owned a grocery business and his father was an investment specialist and later was elected to Congress in 1942.

Warren Buffett purchased his first stock, Cities Service Preferred, for US$38 a share when he was 11 years old. He subsequently went to study under Columbia University’s legendary Benjamin Graham subsequent to his founding of the Buffett Partnership at age 25. From 1957-1968, Warren Buffett generated extremely strong returns of 31.6% CAGR for the partnership and 25.3% CAGR for the Limited Partners, before closing it in 1969.

Warren largely invests across four different categories of investments during his early partnership days:

Controls: Aim to assume a degree or complete control to be active or passive dependent on the company’s future. Rarities but when occur are likely to be significant.

Generals - Private Owner: Generally undervalued stocks that tend to lack glamour or market sponsorship.

Generals - Relatively Undervalued: Securities selling at prices relatively cheap compared to securities of the same general quality.

Workouts: Securities with a timetable. They arise from corporate activity - sell-outs, mergers, reorganisations, spin-offs, etc.

Contrary to popular belief, Warre’s equity investment portfolio during his partnership days was never highly concentrated (i.e. <10-15), and was diversified by count (20-50) even from the beginning with his early Buffett Partnership days (>20, see below). But it was also concentrated by allocation, top 5/10 accounting ~70-80%+, but most often it was due to a number of multibagger winners that were held over long periods of time.

“Over the years, this has been our largest category of investment (generally undervalued securities - "generals")...more money has been made here than in either of the other categories. We usually have fairly large positions (5% to 10% of our total assets) in each of five or six generals, with smaller positions in another ten or fifteen.” - Warren Buffett

Source: 1961 Buffett Partnership Letter

Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway: The Early Years

Buffett continued investing into his 20s and at 32 years old, uncovered a New England textile company called Berkshire Hathaway.

Founded in 1839 as the Valley Falls Company (so named because it resided in Valley Falls, R.I.), the company owned multiple textile companies in the region, and eventually merged into the Hathaway Manufacturing Company in 1888.

After decades of industry growth, Hathaway Manufacturing and Berkshire Fine Spinning Associates merged in 1955. That company, headquartered in Bedford, Mass., employed 12,000 workers and generated more than US$120m in annual revenues, making the newly formed Berkshire Hathaway as one of the most successful textile firms in the US.

Yet by the end of the 1950s, the US textile industry fell into disrepair, and Berkshire Hathaway fell with it, losing seven of 15 plants in the New England region, setting up an uncertain future for the company.

Even with the company’s troubles, Buffett remained a believer. In 1962, intrigued by the company’s long-term business success and strong balance sheet, Buffett via his partnership began buying up Berkshire Hathaway stock.

By 1965, he owned a total of US$14m in Berkshire Hathaway stock, and wound up taking control of the company in May 1965. But at that point, the company was a shell of its former self, with only two manufacturing plants and just over 2,000 employees – down from 12,000 in its glory days.

Change was in the air. Berkshire Hathaway had made its mark as a textile company (its founders had all owned textile firms in the New England region), but by 1967 Buffett was taking the company on a different path, into the insurance and investment sector.

Buffett getting to know about GEICO early, understanding the insurance business and then National Indemnity, a full circle.

Little known is that in 1951, young 20-year old Buffett chanced upon GEICO while reading “Who’s Who in America” and found out that Benjamin Graham was the Chairman of Government Employees Insurance Company (GEICO). Intrigued, he went to GEICO’s HQ and met “Davy” Lorimer Davidson.

Davy spent four hours teaching Buffett about insurance, how GEICO worked, and its enormous cost advantages through direct selling. Soon after, Buffett made GEICO a 75% position in his US$9,800 investment portfolio. Naively, he sold his entire GEICO position in 1952 one year later for US$15,259, to switch into Western Insurance Securities. But in the next 20 years, the GEICO stock he sold grew in value over 130X to about US$1.3m, which taught him an early and dear lesson about the inadvisability of selling a stake in an identifiably wonderful company.

Subsequently, Davy became GEICO’s CEO and took it to new heights, before it got into trouble in the mid 1970s and was threatened with insolvency. Jack Byrne had come in as CEO in 1976 and took drastic remedial measures. Believing both in Jack and in GEICO's fundamental competitive strength, Warren rekindled his first love and bought Berkshire’s first stake in the second half of 1976, and kept making smaller purchases, until it totalled up ~5.7m shares for ~US$28m by 1979.

Warren gradually kept increasing Berkshire’s stakes through the years to 50%, and finally after his first purchase 45 years later, he acquired the remaining 50% in 1995 for US$2.3bn. By that time, GEICO had two extraordinary managers: Tony Nicely, who ran the insurance side of the operation, and Lou Simpson, who ran investments.

Warren’s first insurance company purchase for Berkshire Hathaway prior to GEICO was the National Indemnity Co. in 1967. Warren has shared that if he did not meet Davy and had he been so generous with his time on a cold Saturday, he might never have grown to understand the whole field of insurance, which over the years has played such a key part in Berkshire's success.

Prior to the 1996 acquisition of GEICO of the remaining 50% stake that Berkshire did not own, in 1995 GEICO was one of the biggest winners in Berkshire’s stock investment portfolio and was a 35X bagger, generating US$1.6bn of investment profits. It was slightly shy of the Washington Post (whom young Buffett was delivering newspapers), which was a 42X bagger.

Leveraging on the Insurance Float

Warren and Berkshire perfected the art of using so-called float money from insurance claims (money owed but not paid until claims were settled) to begin investing in other industries. Aside from textiles and insurance, the 1970s and 1980s saw Berkshire purchase stakes in companies in industries as diverse as candy/confectionery (See’s Candy that came with Blue Chip Stamps) and gas and utility companies.

Along came Charlie Munger

A doctor named Edwin Davis and his wife, Dorothy introduced Charlie and Warren in 1959. Charlie was still a lawyer back then in Los Angeles. They predicted that within 30 minutes they would either not be able to stand each other or we would get along terrifically, because of their dominant personalities. But they hit it off right away. They both have strong opinions, have disagreed, but never had an argument at all in 43 years.

Their friendship and business relationship blossomed from there, as Buffett continued building his investment firm and Munger toiled in law. In the early 1960s, Munger said he finally heeded Buffett’s advice about his career path and started his own hedge fund, “Wheeler, Munger & Co.”, which would go on to post an impressive 19.8% CAGR over 1962 -1975, far better than the DJIA’s 5%, according to Buffett’s famous 1984 essay, “The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville.”

Notably, Charlie’s approach was highly concentrated in very few securities, and thus had a more volatile record, but he was also willing to accept greater peaks and troughs of performance.

Along with Charlie Munger, who came aboard as Vice-Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway in 1978, Warren continued to focus on companies with stable, almost predictable long-term growth, while shying away from what everyone else (i.e., the herd) was doing on Wall Street – buying stocks based on assets and cash flow, and in somewhat speculative industries.

Shift from Cigar Butts to Buying Good Companies at a Fair Price

Warren’s preference for early cigar-butt investing of buying declining or poor businesses for a bargain price initially worked well during his early Buffett partnership days with small sums of capital. But the major weakness soon became apparent as they grew bigger.

Cigar-butt investing was not scalable with larger sums of capital. He reflected on his first mistake in buying control of Berkshire. Though he knew its business of textile manufacturing was unpromising, and he only bought it because it was cheap.

By around 1965, he became aware that the strategy was not ideal. Charlie was also instrumental in getting Warren’s to pivot his investing strategy early on. With that, Warren pivoted to buying a wonderful / good business at a fair / decent price, than a fair / poor business at a wonderful price.

Making Mistakes

What stands out to me is that Buffett did make lots of mistakes over the 57 years throughout which he was thoroughly honest about them. Mistakes are all but part of the investing process. There is no hindsight bias, and one cannot expect to make no mistakes.

If one is not making any mistakes, then one is not taking enough risk. You don’t want to be Mark Twain’s frog that never sat again on a stove after being burned. No doubt, mistakes will keep happening in the future, but Warren won’t take “fatal risks” that will cause Berkshire to be wiped out.

What became striking was that he almost never threw good money after bad, reallocating additional capital to reinvest into declining businesses like the textile businesses. Thus the good thing is that the mistakes were painful, became less significant over time, but eventually did not hurt.

“But in the end, we are going to make a lot of mistakes at Berkshire. And we have made them in the past, we will make them in the future.” - Warren Buffett

Source: Berkshire 2004 AGM

A few of the mistakes were spectacularly horrid (e.g. Berkshire itself, the original textile business, Waumbec Mills, another New England textile company, Blue Chip Stamps, Baltimore 4 department stores bought by Diversified Retailing, World Book part of Scott Fetzer, Dexter Shoes, IBM, etc). But the blessing? These mistakes of commission didn’t matter in the grand scheme of things. Because most of their winners largely turned out to be really spectacular (National Indemnity, See’s Candies, Nebraska Furniture Mart, GEICO, MidAmerican Energy, BNSF, etc). Other mistakes of omission range from not buying Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Costco, etc, but too easy to say in hindsight.

Never Selling for Operating Businesses, but not for Stocks

Berkshire Hathaway’s investment philosophy is to invest for the long-term, which is the only term that counts. Very often the literal quote of a forever holding period (see below) comes to mind. However this only applies to the wholly owned operating businesses, which they intend to keep forever.

“We expect to hold these securities for a long time. In fact, when we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favourite holding period is forever.” - Warren Buffet (1988 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter)

But the forever / never selling approach does not apply to the partially owned stakes in the common stock portfolio, where Warren has bought (when they were cheap) and sold stocks (when they become expensive) a few within a couple of years. Petrochina is one of the glaring examples that comes to mind where it was an 8X (US$4bn sale in 2007 versus US$488m purchase in 2002/03) and sold because it was overvalued at a US$275bn market cap.

Thus it is important to differentiate their forever investment holding period approach for Berkshire’s operating businesses versus the common stock holdings. They will keep their operating businesses forever, but not their stock holdings, though they generally would want to keep it for as long as possible.

“But in terms of building Berkshire for the long-term, we just like adding our earning power-- big chunks of earning power from operating businesses, which we are going to keep forever. So none of the stocks are forever. But they are generally for the very long term.” - Warren Buffett (2014 CNBC Interview)

Final Words.

I wish both Warren and Charlie continued good health, and I am really appreciative to be able to learn from these two investing greats.

Thank you Warren and Charlie! I hope they can continue to share and impart knowledge to us with more years to come and keep growing Berkshire and grooming its future leadership.

I am looking forward and excited to head up to Omaha this coming week for the 2023 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting to see them in person. Swing by and say hi if you see me around!

PS: This article is written by me, without the help of any ChatGPT, and will probably have some mistakes. If there are any glaring ones, please do not hesitate to reach out to me. And if there are any other thoughts/observations about something that you feel is important, that I missed capturing, please feel free to share! I am always happy to improve, and invert to see it from a different viewpoint.

30 Apr 2023 | Eugene Ng | Vision Capital Fund | eugene.ng@visioncapitalfund.co

Find out more about Vision Capital Fund.

You can read my prior Annual Letters for Vision Capital here. If you like to learn more about my new journey with Vision Capital Fund, please email me.

Follow me on Twitter/X @EugeneNg_VCap

Check out our book on Investing, “Vision Investing: How We Beat Wall Street & You Can, Too”. We truly believe the individual investor can beat the market over the long run. The book chronicles our entire investment approach. It explains why we invest the way we do, how we invest, what we look out for in the companies, where we find them, and when we invest in them. It is available for purchase via Amazon, currently available in two formats: Paperback and eBook.

Join my email list for more investing insights. Note that it tends to be ad hoc and infrequent, as we aim to write timeless, not timely, content.